Two Mothers

Pop on over to this site for my latest essay. Thanks to Michelle Madrid-Branch for inviting me to contribute–and for giving me a chance (with a deadline) to write about an experience I had in South Africa that I’ve been thinking about ever since.

The Home

I’ve been here twice before. 2678 W. Washington Boulevard in Chicago’s East Garfield Park neighborhood. The first time, maybe six years ago, I got out of the car to walk along the iron gate in front of the property. I didn’t know much about the house then except that our birth mother had lived there for several months when it was a home for unwed mothers, and that it was no longer a home for unwed mothers. The Florence Crittenton Anchorage closed in 1973, not long after she had walked out the door, heavy with the two of us, and kept going. I retraced her steps to the gates, surveying the beautiful old Victorian mansion with its round spire in front, the red brick coach house next to it, the overgrown grass courtyard. It all looked abused, like it had borne too many secrets.

The second time, a couple years later, I took my sister to see it. We rolled by slowly, bearing witness to our pre-being through the glass of her car windows. It took more years for me to learn something of the property’s history, and it was not an easy search. Once, a clerk in the Cook County Assessor’s office, after searching for a property PIN to match the home’s address on West Washington Boulevard, told me the address didn’t exist. I’ve seen it with my own eyes, I told her. She looked at me and shrugged. We eventually found it, listed under a vacant lot on the street behind it. I also discovered that the property had changed hands among social agencies several times after the Anchorage closed—mostly serving the same purpose as when our birth mother was there: sheltering people with nowhere else to go.

Yesterday, the man who currently owns the property let me in through the gates. For the first time, I passed through to the inside where she had been. The property was in shambles when he bought it—unkempt and looted—with wires ripped from the walls. The fireplace mantles were gone; a section of the stately wooden banister that winds its way up three flights of stairs, missing. He’d recently added a new roof, but the floors were soft and crumbling and covered with plaster that had fallen from the walls and ceilings. He told me he intends to restore it, turn it into apartments. How long will that take? I asked. After all, I know nothing of these things. Nine months, he said. Nine months.

On my phone I had copies of floor plans from the late 1960s that I’d found in a Chicago library, and by way of a trade for the favor of allowing me inside, I showed the owner: Here was the door where the women knocked for help, the place where social workers recorded the bare details of their stories on intake cards, the kitchen, the food pantry, the visitor’s room and library, the rooms where the women stayed, where my birth mother stayed.

On the second floor of the main house, in one of the bedrooms, I ran my fingers along evergreen paint exposed beneath layers of pink paint and crumbling plaster. I wondered if this green underneath was the color it was when she was here (it was, she later told me). As if he had read my thoughts, the owner picked up a large peel of green from the floor and handed it to me. A souvenir. As we walked around the house and the one-story dormitory attached at the back, I held the paint gingerly between two fingers. But it was so fragile that it kept crumbling as I hopped over holes in the floor and debris lying on the ground. By the time we reached the long hallway in the dormitory, I barely had any left, only the tiniest fragment the size of a small insect’s wing. Here there had been water damage and a fire and more looting. In one room was a pile of wooden dressers with drawers removed, leaving empty eye sockets, and a crib. We turned on our phone flashlights to see, silently peeking into rooms. The end of the hallway turned left toward more rooms and access to a courtyard where, I knew from my research, there were sometimes barbecues and parties for the women who stayed there. But the hallway that led out was even darker, the floor more unstable, and the owner told me it was just more of the same. I turned back, thanking him for the tour, my face steady and professional, not too yearning, and carried my wing out through the front gates and onto the street.

Back at my sister’s house, I folded it between two pieces of clear tape, this piece of the house where our birth mother stayed, waiting for us to be born. But by the next morning, I couldn’t find it anywhere. It, too, was gone.

Caledonia

When the car hit a slick spot and spun around in the middle of the highway, I recorded the metaphor to share with her one day—this image of a little white car in white-out conditions on a snow-covered Minnesota highway facing backward. So much white, like the blank of a new page. While I managed to get the car turned around and moving, I am, twenty years later, still facing backward. She already knows that we were driving in a blizzard because her mother later told her the way mothers tell their children when they are old enough to ask. But what she may not know—and I am here to tell it because I was there—is that I had both hands on the steering wheel in a terrified but determined grip. Her father was somewhere else, so I was responsible for her mother, who was in the seat beside me, breathing hard and wincing from a pain I was too young to understand.

When the car hit a slick spot and spun around in the middle of the highway, I recorded the metaphor to share with her one day—this image of a little white car in white-out conditions on a snow-covered Minnesota highway facing backward. So much white, like the blank of a new page. While I managed to get the car turned around and moving, I am, twenty years later, still facing backward. She already knows that we were driving in a blizzard because her mother later told her the way mothers tell their children when they are old enough to ask. But what she may not know—and I am here to tell it because I was there—is that I had both hands on the steering wheel in a terrified but determined grip. Her father was somewhere else, so I was responsible for her mother, who was in the seat beside me, breathing hard and wincing from a pain I was too young to understand.

Months before at the bar on Grand Avenue, her dad and I were drinking Leineys while her mom nursed her water, the three of us tossing around baby names. Caledonia was on the table, and so was Dakota, but she would become Caledonia Rose. In the weeks before her birth, her dad played Dougie MacLean’s “Caledonia” over and over in the dining room in their house in Minneapolis where I spent so many evenings escaping the broken-heart loneliness of my own life while waiting for hers to begin. I’ve been telling old stories, singing songs/That make me think about where I came from/And that’s the reason why I seem/So far away today.

Long after I moved away, leaving the three of them behind but taking with me all that I had witnessed, “caledonia” was the password to all of the accounts of my life. Our lives forever after separated, I knew no one would ever guess that she was the first child to open my heart to love. I would not feel that kind of love again until I pulled my children into the world with my own hands, vowing to hang onto their slippery bodies and to every last detail.

There are no reliable narrators in the story of my own birth, and so I bore witness to Caledonia Rose’s beginning with a determination sprung from my own sense of loss. But the thing is, Caledonia never needed anything I had saved. She hasn’t spent years of her life trying to track down eye-witness accounts of life before she knew it, has never once asked me for mine—or maybe even considered that I might have one.

But I saved it for her anyway: I woke in the half-second space before your mother knocked on the door of the room where I was sleeping, somehow sensing what she was about to say: Her water had broken, and we needed to get to the hospital. I jumped from your sister’s bed, my heart racing, and ran to shovel the walk, brush the snow from the car, throw your mother’s bag in the car. I took hold of your mother’s thin arm the way I knew to walk my grandmothers, simultaneously guiding and praying. We spun out on the way to the hospital, at one point facing backward on the highway. The hospital is a blur of images that I’ve tucked away to protect your mother’s privacy. She put on a gown. Sat on the toilet. Flipped off a nurse. Held her belly in agony. Made phone calls. Later in the afternoon, the mood changed from celebratory to desperate, and your father arrived. I remember being at the end of a hallway, leaning against a heater, my back to a window. The walls were the same green as the walls of the hospital where I was born, so I need to tell you that I am not sure if they were green at all, but only because, waiting for you to born, I could not stop thinking of my own birth story—and that story is all dreams and no truth. Your father told me to go home in a tired voice that was neither kind nor mean, and I drove myself back to my apartment in the snow. I had no money then, but I splurged and bought myself a carton of curry mock duck from a Vietnamese place that is no longer there, down the street from the tavern where we picked your name, which is.

This is no longer your story, but I will tell you that I walked to get the food instead of driving because of the snow, and when I got back to my apartment, I realized it wasn’t mock anything but real duck. I cried when I figured that out because I was too tired and hungry to trudge back to the restaurant in the deep snow, and I’d spent all this money on food that wasn’t for me. Instead, I tossed the meat in the trash and went to bed. By the time I woke, the doctor had split your mother open, just as the doctor had done to mine. As your mother hobbled up and down the stairs in the long weeks of recovery after your birth, I was there, helping to care for you, helping to care for her. I was there because I wanted to be but also because I had nowhere else to go. The point is, I was truly there, squeezing light from the darkness with my very own eyes.

Grace

The first dog lasted less than two weeks. And by “lasted,” I mean, “lasted.”

Four days after he became ours, Benji (short for Benjamin Franklin) ended up at the vet hospital. He had been vomiting and unable to eat since the moment we brought him home. For the next six days, we visited him almost every night in a place between touch and go. When the vet called one afternoon to say that Benji had sepsis and wasn’t going to make it, I picked up the two older boys after school and raced to the hospital, praying that we could usher this dog out of the world wrapped in love. We arrived just in time.

We’d been talking about getting a dog for years—well, mostly it was one of our middle boys talking/begging—but I knew we’d eventually say “yes” because when you grew up with dogs adopted from shelters or plucked from the streets and now you live in a big house in the suburbs with four boys who aren’t allergic to anything under the sun, then the laws of the universe will eventually deed you a dog.

I’m going to acknowledge now that my thoughts about adopting a dog from a rescue—for that’s exactly what we did and what I believe we were meant to do—are completely linked to my own adoption. You may counter that plenty of people who know nothing personally of people adoption choose animal adoption or that people who were adopted buy animals from a breeder. That is also true. There’s no judgment here, only a firm belief that for me, historical cause and psychological effect are inseparable. I came into this world in a state of suspension, and so I am drawn to the animals who are dangling, too. We caught Benji at the very end of his life, but we caught him.

After Benji, came Grace Kelly, and let me be honest, Grace-Kelly-the-Beagle is a tough dog to love. No, that’s not right. Grace Kelly is loved. But she is a tough dog for us to handle. We are in over our heads. Every time I catch myself wondering what the heck we were thinking when we said “yes” to Grace, I am flooded with guilt and a deeply personal understanding of what it’s like to be given up and taken in. I don’t care that Grace is a dog. What does that mean anyway? Grace needs a family who will love her unconditionally and will not abandon her again. Grace also needs a family who will patiently deal with the behavioral and house-training issues that make living with her such a challenge. Grace needs a family who knows a lot more about dogs than we do, with the flexible schedule (and cash) needed for rigorous training. Oh, God, maybe it was Grace who got the raw deal after all.

The truth is, I see Grace’s life the way I used to see my own: as a transparent window into what-if’s and might-have-been’s and if-only’s. What if Benji hadn’t died? What if I had said “yes” to the Chihuahua the rescue offered after Benji died? What if I hadn’t messaged back, “Is Hope available instead?” (It’s not lost on me that the shelter had named our dog Hope before she became our Grace.) What would Grace’s life be like if somebody else had adopted her instead? I can’t imagine that a cute purebred beagle with a sweet-as-pie disposition would have been hard to place.

The truth is, I see Grace’s life the way I used to see my own: as a transparent window into what-if’s and might-have-been’s and if-only’s. What if Benji hadn’t died? What if I had said “yes” to the Chihuahua the rescue offered after Benji died? What if I hadn’t messaged back, “Is Hope available instead?” (It’s not lost on me that the shelter had named our dog Hope before she became our Grace.) What would Grace’s life be like if somebody else had adopted her instead? I can’t imagine that a cute purebred beagle with a sweet-as-pie disposition would have been hard to place.

But adoption doesn’t work that way. Or it shouldn’t. Unless someone or something is in imminent danger, there aren’t do-overs. Sure, Grace is a dog, not a child, but all that means to me is that she doesn’t stay awake at night worried that if she messes up, we will send her back.

On difficult days, my husband and I ask each other, “What do we do? What do we do?” We really have no idea what to do other than to keep trying our best to make things work for Grace.

Because that’s something I understand about adoption, too. There are always far more questions than there are ever answers. Grace is the salvation that comes even when you don’t understand it or don’t deserve it.

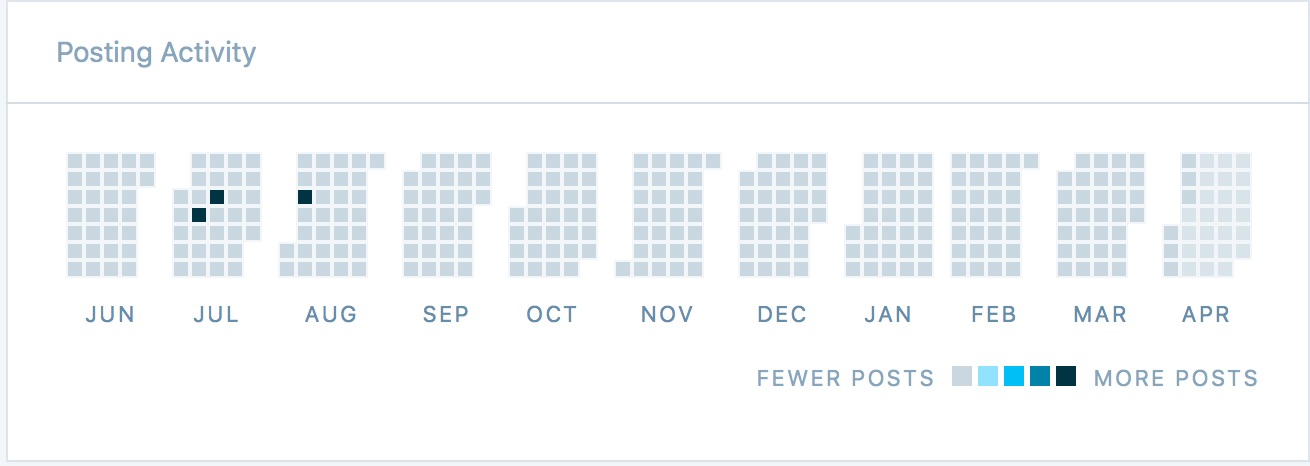

Stuck

If it is possible to remain still in motion, that is where the story of my reunion with my birth family both stays and moves. Adoption is Newton’s fourth law: Every story in a state of stillness remains in a state of stillness even as it moves. My story is still, but my life moves. What is there to say to that? Sound doesn’t travel in a vacuum, but light does.

To some extent, I’ve returned to where I’ve always been. I think of the photographer’s backdrops in the commercial portrait studio, pulled down as needed, rolled back up when not. Adoption is currently tucked away. Instead, I’ve pulled down the familiar backdrop of my childhood in front of which I almost always pose(d) content.

We hardly talk any more, my birth parents and me. There are no plans to see one another again. If it happens, it happens; if it doesn’t, it doesn’t. Galileo called it inertia. My last words to my birth brother, in an email nearly eight months ago, were “Never mind!” Out of context, it seems rude, but it wasn’t—it was just that: “Never mind!” When you take a photo, you’re not worried about the audio, right? It’s the light that matters.

Never mind any of us, in fact. Where we have been, where we are, where we are going—all of that remains tucked out of sight while we go on living the lives we were living before we knew who we were.

Of course it’s not the same. It can never be the same. Now we live knowing full well who we are. The story absorbs this knowledge and the stillness. “Being stuck” simply becomes a part of it.

I can say it doesn’t matter, but it does.

Oh, never mind.

Just know: I’m still here, stuck and moving, silent and writing.

Results

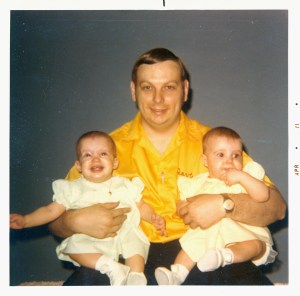

Less than a month ago I sent away for a twin zygosity test from a company that specializes in analyzing DNA for twins and triplets. I sent away for a bit of science to tell me if my twin and I were fraternal or identical

Less than a month ago I sent away for a twin zygosity test from a company that specializes in analyzing DNA for twins and triplets. I sent away for a bit of science to tell me if my twin and I were fraternal or identical

For a variety of reasons, straight answers are hard to come by in adoption stories, and I have spent the better part of five years trying to track them down in my own story. The appeal of the zygosity test is that it isn’t loyal to anything or anyone. It isn’t affected by time and emotion. It has no intent, no desire, other than to be accurate.

The adoption counselors at Lutheran Child & Family Services told my parents that we were fraternal twins. Two sacs. Those are the words in the notes my mother took during a conversation with one of the counselors. Two sacs = fraternal, she wrote. Our birth mother was told that, too. Definitely fraternal, she confirmed when I asked shortly after meeting her.

In fact, even today, with all the leaps in scientific understanding, some medical professionals still confuse the presence of two amniotic sacs as evidence of fraternal twins. That’s not always the case, though. One-third of all identical twins are born with two separate sacs, indicating that a single fertilized egg split into two before the fifth day following conception, at which point the sac forms, one around each twin. For the other two-thirds of identical twins, that splitting occurs between the fifth and ninth day, after the formation of the sac; in that case, the twins share a single sac.

One summer, during college, I took a biology class at our local community college with one of my high school science teachers. In high school science classes, I could barely get through the units on genetics. As somebody who was adopted, I felt alienated, and depressed, by the discussion. But in the college class, Mr. Thistlethwaite, who knew my sister and me, reminded me that I had something to go on when it came to questions of heredity and genetics. I had my sister. And so I dove into the unit and emerged convinced that my sister and I were identical, despite what we had been told, despite all of the differences people saw in us because, well, because we were fraternal. I went home from class one day and broke the news to my mom. “That’s not what we were told, honey,” she said kindly.

Two weeks ago, I handed my sister a test tube and six cotton swabs and told her to swab. I did the same. Three swabs on the inside of each cheek, once before dinner and once again the next day before breakfast. There was no fanfare to the procedure. We were racing to do it before one of the six boys between us interrupted us with the crisis of the hour. I put the tubes in an envelope, and we mailed it from a box in front of the post office in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

When I opened the e-mail today with the DNA results, I was secretly hoping that science would confirm what my heart said. If that weren’t the case, I still had irrefutable proof about something related to my birth, something that hadn’t been incinerated or amended or lost or forgotten.

Test Results #20556-150715 were based on an analysis of 15 standard DNA markers used in human identity. That analysis indicated that there is a “greater than a 99.9% probability that the twins are monozygotic.”

In other words, my sister and I are identical twins.

Immediately I called my twin to tell her the news.

“I feel like I’ve been born all over again,” I teased.

I could hear her shrug through the phone. “It only confirmed what I knew all along.”

But in the silence that followed, neither of us could stop smiling.

Twins

Last week the New York Times Magazine ran an engrossing article titled “The Mixed-Up Brothers of Bogotá” about four brothers who, due to an accidental swap at a hospital when the boys were newborns, were raised with the wrong twin.

Last week the New York Times Magazine ran an engrossing article titled “The Mixed-Up Brothers of Bogotá” about four brothers who, due to an accidental swap at a hospital when the boys were newborns, were raised with the wrong twin.

What strikes me most about the story of the Bogotá twins is how fiercely they continue to hold on to one another, even after discovering that they each have an identical twin and share absolutely no genetic connection with the brother raised alongside them. In other words, there’s no wrong twin; there’s only the twin each of them loves and the twin each of them lost to the mix-up. After learning about one another and eventually meeting, one of the twins tells the brother with whom he grew up, “You’re my brother, and you’ll be my brother until the day I die.” Another twin, sensing how unmoored his brother is by the discovery of their identical twins, has a portrait of his brother tattooed upon his chest.

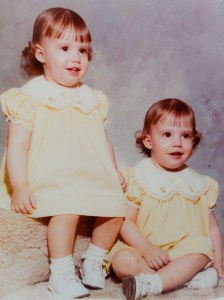

My sister and I are not identical, at least not according to what my birth mother was told by people who didn’t always tell her the truth. There’s no reason to doubt what my birth mother was told, but there’s no proof, either. Several years ago, the head of Medical Records at Illinois Masonic Medical Center confirmed that our records had been destroyed, leaving no trace of our birth in the medical system.

Fraternal twins, like my sister and me, have no more of a genetic link than any siblings do, no more than, say, my sister and I have with our biological brother whom we learned about when we met our birth parents. As the article points out, the formation of fraternal twins is “mundane.” But wait–it’s more complicated than that. As the article also points out, genetic research has shown that biological influences and environmental influences play an equal part in shaping who we are. Moreover, when you throw in the complex nature of our “genetic circuitry,” the way our genes respond to and are even transformed by our environmental experiences, all bets are off. Science aside, science included, what makes a twin a twin is really hard to say.

Fraternal twins, like my sister and me, have no more of a genetic link than any siblings do, no more than, say, my sister and I have with our biological brother whom we learned about when we met our birth parents. As the article points out, the formation of fraternal twins is “mundane.” But wait–it’s more complicated than that. As the article also points out, genetic research has shown that biological influences and environmental influences play an equal part in shaping who we are. Moreover, when you throw in the complex nature of our “genetic circuitry,” the way our genes respond to and are even transformed by our environmental experiences, all bets are off. Science aside, science included, what makes a twin a twin is really hard to say.

So much of my own identity is connected to my being a twin. Even though my twin and I unhitched ourselves from one another at age 18, attending different undergraduate and graduate schools and setting off on different career paths, being a twin has influenced so much of who I am and what I have done.

Our adoption is tangled up in there somewhere, too. My own ferocious loyalty to my sister has a lot to do with the fact that she is my twin but also to do with the fact that, growing up, she was my biological other; she was my only biological other. And yet, when it comes to the rest of our family, I don’t give a hill of beans about biology. They will be my family until the day I die.

My birth brother once asked me once about this contradiction. I had no answer then. I have no answer now. As with the Bogotá twins, sometimes love, and family, passes human understanding. It is both bewildering, and miraculous, and all you can do is hang on for the ride.

Still, l wonder: Are my sister and I identical? Are we fraternal? Unlike so many unanswerable and forgotten parts of our story, this is one that the present can satisfy more accurately than the past.

As a birthday gift to us this year, I sent off for a Twin DNA Zygosity Test that will answer this question with 99.9 percent accuracy. Monozygotic or dizygotic. We should know in about six weeks.

And whatever we find out, it won’t matter at all. We already have what does.

Solomon’s Dilemma

A story titled “A Father’s Struggle to Stop His Daughter’s Adoption” appeared earlier this week on The Atlantic Monthly’s web site. It’s a riveting read about a birth father’s quest to gain custody of the daughter he loved from the beginning and whom he intended to raise. Unbeknownst to the father, and without his consent, the birth mother gave the baby up for adoption. The father, Christopher Emanual, got the child back nearly three months later, but with laws and cultural attitudes stacked against single fathers, and in this case, a father of color and a child of mixed race, you get the feeling that he could just have easily not gotten the baby back.

The very title of the article speaks volumes. It’s not called “A Father’s Struggle to Gain Custody of His Daughter.” It’s called “A Father’s Struggle to Stop His Daughter’s Adoption.” Wait, what? Stop adoption? As a journalism professor, I’m well versed in the short attention span of readers and the power of provocative headlines, so I understand the magazine’s choice of wording on that level. On another, though, it pokes at a narrative about adoption that continues to hold firm in American culture. It’s a headline designed to compel the reader to dive into the extraordinary madness of a stopped adoption. I mean, who in the world stops adoption? And why?

When I was younger, this article would have stirred a familiar panic, however irrational, that somebody out there was going to take back my twin and me, was going to yank us from our family, our life, our identity. Then, our birth family did not have names or faces. They were flat, undeveloped characters in a story shaped by partial truths and deceptions and, mostly, by my own imagination. The only one who inspired any kind of sympathy was my birth mother, and even then, I was sympathetic toward a stock character, toward an ideal. Back then, I understood adoption in these simple terms: It was a process by which those who could not care for their children gave to those who could, and everyone was better off for it. End of story.

My twin and I were better off for it, but adoption is never the end of the story. That’s what I’ve come to realize most keenly in the last few years as both my reunion with my birth family and my broader understanding of adoption have chipped away at my naiveté. People go on living in various stages of heartbreak and recovery for the rest of their lives. And the child who was adopted and becomes the adult who was adopted isn’t the only one plagued by what if’s and if only’s, by the different versions of life left on the cutting room floor.

Our birth father has long maintained he would have raised us if he had known about us. In 1970, that would have been difficult. Men did not have rights to children they conceived outside of marriage. He would have been pushing against a cultural mountain that privileged my married adoptive parents over him and my birth mother, despite the fact that my birth parents eventually reconnected and wed 10 months to the day after my sister and I were born. And the awful, selfish truth of the matter is, in my desire to keep all that is good and dear to me, I’m almost grateful I was born in a time where my birth father never stood a chance. On the flip side, when my birth father went on to adopt three of the four children he raised, he was the good guy again, the guy with rights, the guy everyone would have rallied behind, including me.

Recently, my birth father wrote to me, “You will always be a daughter that I didn’t have the opportunity to raise and enjoy. I’m sad about that….” I’m sad for him, too. Somehow, I can manage to feel both his devastation over what he lost and a fierce, self-preserving rejection of it. Because to be the daughter he raised and enjoyed, I could not also be my own father’s daughter. I couldn’t belong to both.

Isn’t that the crux of these recent stories of contested adoptions that make headlines? Too many people–birth fathers, too–want the baby for their own. It’s a modern take on King Solomon’s Dilemma. In this case, though, nobody is willing to cut the baby in two–though the various sides might make a go of it rhetorically. You also can’t, as Solomon did, so simply root out the wrong parent or the wrong life even if the law eventually favors one side or the other.

So in the absence of a clearly horrible choice, and without the evidence of a future life reviewed in hindsight, King Society and King Law, mired in their own socio-political moments, must decide between two decent possibilities, between two potentially happy lives. And whatever King Society and King Law decide, that is the life, and the father, the child is handed; that is the person she becomes.

And so here we are, ordered, adjudged, and decreed.

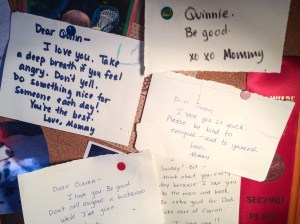

Epistles

I’ve been saving letters and postcards since I was a child. In a tiny closet in my attic study are hat boxes filled with these relics. Most of them are from my twin, my mother, and my grandmothers, but I have decent-sized stacks from others, including my best friend Emily, who still writes to me several times a year, and my husband, who was living in a different city when I met him. Most of these letters were written during years when I was away from home and from people I loved, college and graduate school years in which long-distance phone calls were 25 cents a minute on the MCI Friends & Family plan and my e-mail address was jes97003@uconnvm.uconn.edu. The popular world of text messaging was still 10 years off. Back then, too, I had plenty of time to write, and to wait.

I’ve been saving letters and postcards since I was a child. In a tiny closet in my attic study are hat boxes filled with these relics. Most of them are from my twin, my mother, and my grandmothers, but I have decent-sized stacks from others, including my best friend Emily, who still writes to me several times a year, and my husband, who was living in a different city when I met him. Most of these letters were written during years when I was away from home and from people I loved, college and graduate school years in which long-distance phone calls were 25 cents a minute on the MCI Friends & Family plan and my e-mail address was jes97003@uconnvm.uconn.edu. The popular world of text messaging was still 10 years off. Back then, too, I had plenty of time to write, and to wait.

There’s one letter, though, that I’ve never been able to find despite a dogged search through all of the boxes and bins of memorabilia that I’ve lugged into my present. It’s a letter that I wrote to my birthmother when I was around 12, the age my oldest son is. He writes e-mails to me like: “Dear Mom, November 26 is Mrs. Spinelli Day. I need to bring in a $1 by next week. Love, A.” The first letter I ever wrote to my birth mother begins, “Dear Lady,” and launches into a long explanation of my difficulty in knowing how to address a nameless person. For the longest time, that letter was sealed in an envelope and tucked between the mattresses of my childhood bed. It was one of those letters that needed to be written, even if I knew it would never be read, because somehow by writing it, by putting words into the universe, I was convinced my birthmother might hear them. It worked for my sister and me–this talking to one another without speaking–and so I hoped it might worked for “Dear Lady,” too. In that sense, it was more prayer than letter, promising that I had turned out well, that I was loved and happy, that I harbored no ill will.

By the time I was a sophomore in college, my letter to my birthmother was angrier. It’s less of a prayer and more of a late adolescent howl. It’s a letter missing the context of a full life, though no less real for its moment. Several years ago my birthmother asked me if I had found the “Dear Lady” letter I had told her about. The angry college letter is all I turned up. I quoted her a few innocent lines from the letter, but I didn’t tell her what it really said. By the time I finally knew who she was, I was somewhere other than the emotions of that letter. And she had a name.

There is a hatbox now for my birth family although it’s nearly empty. Most of our correspondence has been by e-mail. In fact, our first words to one another came packaged in e-mails that began tentatively, wondrously. She called me Jenny. I called her Mrs. D. We didn’t talk on the phone for four more months. I’ve saved over 1,000 e-mail messages in the last five years, mostly from my birthparents and their son, my biological brother. I communicate now most regularly with my birthparents’ daughter, but that occurs in the ephemeral space of instant message and text.

These days, other than the communication that is hard to hold onto, I am confined to notes of last resort, to the scribbles I leave my boys in the final moments before I head off on a trip. In our daily leave-taking, my last words are spoken. “Be kind!” I say as they head out to the door to school, uttering my daily mantra. They’re smart boys. Most days, they’re good boys. So I trust that everything else will fall into place if only they remember to be kind.

But when I’m about to leave them for an academic conference or for a research trip or, as I did last December, for travels across the world to meet my nephew in an orphanage in Morocco, my compulsion is fueled by an inexplicable panic. What if something happens to me? What if they never see me again? I think of them as I imagine my birthmother thinking of me all those years, with hope and yearning from an insurmountable distance. What I have to say must be written down. After all, I reason, if something happens to the Mother of Flesh, then the Mother of Words can take over.

“Dear boys, Leaving you on Christmas is hard! Please be good for Dad and to each other. Be kind! It’s the most important gift you can give to the world on this day of gifts. I love you. Mommy will keep you close to her heart. You do the same.”

And so I become that child of adoption once again, leaving my boys epistles to tack onto their bulletin board, leaving my boys with all that I have: my heart and a name. Love. Mommy.

Imperfections

I recently came across a Huffington Post feature titled “30 Perfectly Imperfect Holiday Card Outtakes” that immediately reminded me of my own decade of perfectly imperfect holiday card outtakes that I have been collecting since, well, since I began taking holiday card photos of my perfectly imperfect children. In fact, I have so many of these perfectly imperfect holiday card outtakes that I’m surprised that the Huffington Post editors didn’t contact me directly for material rather than bother with crowd-sourcing from their Facebook readers. While many of the HuffPo contributions made me laugh aloud, I knew, oh, yes, I knew, I could compete. You want outtakes? I’ll show you outtakes.

Every year, come Christmas card photo taking time, I swear I’m just going to haul the cherubs over to Picture People and let somebody else deal with them. This holiday chore, which I once truly enjoyed, has grown exponentially difficult the more (closed) eyes and (troublesome) temperaments we’ve added to our family. But then I’d have to purchase the photos from Picture People. Why buy marginally better photos when you can get marginally worse ones yourself–for free? Besides, I’m the sort of person who does not like to be defeated, especially by her own children.

2014

Now, when I suggest that I can get my own photos for free, I am simply referring to the cost of my trusty Canon 7D, long paid for, and to my labor. I’m not referring to the price tag of the emotional toil of this endeavor, nor to the therapy my kids may one day need for enduring it. There’s also the cost of couples therapy for the years that I mistakenly involve my husband in the outing. My spouse is the right man for so many situations, but Christmas card photo taking is not one of them. He’s got too much couth, and too little patience, for the roles I assign him: clanging spoons over my head to get the baby to LOOK. AT. THE. @%#$. CAMERA; jumping up and down while holding Jingle Bells so the toddler will SMILE. FOR. THE. @%#$.. CAMERA; remaining Christmas-cheery-cheerful as the whole lot of them breaks down and the five-year-old comes charging at THE. @%#$. CAMERA. That means I am often the one simultaneously hopping up and down, making deals through gritted teeth–if I get a good one, you can watch TV for the rest of the day/week/year/your life—and trying to snap a decent photo.

While at Valley Forge National Historical Park earlier this fall with my oldest son’s robotics team, I got the hair-brained idea that a Revolutionary War battlefield would be the ideal backdrop for a Christmas card photo. After all, nothing invokes the misery of the 1777-1778 winter encampment like four boys between the ages of one and twelve trying to cooperate for a single perfect photograph. Indeed, what better metaphor for the Christmas card photo shoot than the dogged determination and perseverance of the continental soldiers at Valley Forge?

To make a long story short, I lost the battle. Friedrich Wilhelm Rudolf Gerhard Augustin von Steuben himself could not have saved us from ourselves. When I showed the boys the photos I had taken, they cried and begged me not to use them. I admit, I momentarily considered accepting bribes. How much is it worth to you to keep these photos off of Shutterfly? Instead, I settled for the more ethically responsible and mature, “I told you so.”

A week later, I tried a new tactic. I told the five-year-old, who was largely responsible for the ruined shoot at Valley Forge, that he was in charge. I said we would do whatever he wanted, and I gave him everything he asked for, except the camera. So, on a cloudy Sunday morning, before the sun rose overhead and ruined everything with its bright, chipper light, I ordered my husband to stay put while the rest of us trudged out into the frosty backyard. The five-year-old wanted all of the brothers to pose like reindeer, wearing reindeer ears, on the roof of their log cabin playhouse. He wanted a Santa hat on the chimney. He wanted a singing, dancing stuffed Rudolph in the picture. He didn’t want nice clothes or matching clothes. Frankly, he probably would have preferred no clothes at all. To keep the peace (a.k.a. giving in to prevent tantrums), we went along with it–although I allowed the twelve-year-old to ditch the reindeer ears in honor of his pre-teen dignity. (The five-year-old threw a mini fit over this insult but eventually recovered.) And, to cut to the chase, I got the photo. It’s not worth showing here because, well, it’s too good to be true.

I’m keeping the outtakes from Valley Forge to add to my ever-growing collection. Other than to honor the historical record, and perhaps to trot them out at a graduation or wedding some day, why hang onto them? Because they say more about us than one good photo that, by some Christmas miracle, turns out just right and makes its way to the mailboxes of our friends and family each year. Because, one day, when the wounds have healed and all Wii privileges have been restored, I hope we can sit back and appreciate these snapshots of our perfectly imperfect family enjoying (surviving) this wonderful life.